By: Lawrence Bopp

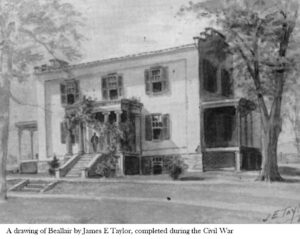

On the 6th of November 1860, Lewis and Ella Washington were wed at her family residence of Clover Lea in Mechanicsburg, Virginia. Shortly thereafter, they moved to Beallair in Jefferson County to establish their home together.

On the 6th of November 1860, Lewis and Ella Washington were wed at her family residence of Clover Lea in Mechanicsburg, Virginia. Shortly thereafter, they moved to Beallair in Jefferson County to establish their home together.

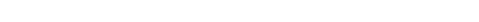

We know Lewis and Ella were distant cousins; Lewis was George Washington’s great-grandnephew and Ella a descendant of one of the first president’s sisters, Betty. Certainly, they had met each other during various family gatherings and some kind of closeness developed. Lewis was widowed in 1844 when his wife Mary Ann Barroll died giving birth to his daughter Mary Ann. He sent his children to live with their maternal grandparents in Baltimore while he labored to keep Beallair running. He exhibited some frustration with his role as gentleman farmer by offering to sell his property several times but failed to do so.1

There are few clues that help us piece together the courtship that brought together 26 year-old Ella with this man nearly twice her age. In those days, she was considered well beyond the usual marriageable age, and it was also not uncommon for young girls to marry much older men. The Jefferson County Museum recently acquired a collection of letters from the family of Lewis Washington, one of which could provide insight into Lewis and Ella’s relationship.

In October of 1859, Lewis rose to prominence when he was taken hostage by members of John Brown’s provisional army, who liberated men Lewis enslaved and confiscated heirlooms passed down from George Washington. Lewis was held in the Harpers Ferry Armory’s engine house as a captive and was finally freed when US Marines stormed the building. He put on a show of bravado by straightening up his appearance and putting on his kid gloves before exiting the building to the cheers of his fellow citizens.

In October of 1859, Lewis rose to prominence when he was taken hostage by members of John Brown’s provisional army, who liberated men Lewis enslaved and confiscated heirlooms passed down from George Washington. Lewis was held in the Harpers Ferry Armory’s engine house as a captive and was finally freed when US Marines stormed the building. He put on a show of bravado by straightening up his appearance and putting on his kid gloves before exiting the building to the cheers of his fellow citizens.

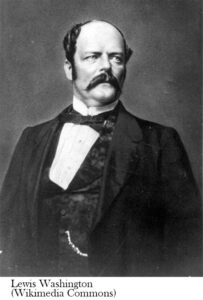

Lost to history but of great importance to Lewis, Ella Bassett, hearing of his travails, had written him a letter of condolence upon his unfortunate experience as a captive. In one of the letters now in the Museum’s collection, Lewis responded quite affectionately on October 30th, less than two weeks after the ordeal to “My dear Cousin Ella.” He reveals that he is staying with the Turners at Ripon Lodge instead of Beallair, for fear that abolitionist Brown sympathizers might again try to kidnap him or cause him harm. He apologizes for his brief response to her missive and bemoans the fact that he is worn out not only from the ordeal but also from having to attend court and testify nearly every day. He promises to write her a lengthy letter when he can saying, “I will take the earliest opportunity to do myself the pleasure to write to my Sweet Cousin Ella…”2

A Transcription of the letter is below:

Rippon (sic) Lodge- October 30th 1859.

My dear Cousin Ella:

I write from the residence of my particular friend Mr Turner-where I have been staying since my release, as I am the most important witness against the willful marauders, my friends insisted that during the trial I should not remain at home where an effort might be made by the abolitionists to effect my capture to hold my life against that of Brown. So much for my addressing you from this place- Now my Sweet Cousin, I cannot express to you the pleasures your letter afforded me-it manifestly shows your warm generous heart, more so than could be shown by conversation. And I am sorry that my indisposition (back of letter) incident to my exposure during confinement for thirty-three hours, renders me unfit to reply to your sweet letter as I should desire. For I assure you I am sick & sore, and have been compelled to attend court every day as a witness so hoarse that I could scarcely give in my testimony. So Dear Cousin you must take the will for the deed and believe it would give me essential pleasure, if I was able, to write you a long letter.

I shall have to attend court every day probably for a week to come and have to save myself as much as possible-Write to me soon, and when our troubles are over & I am once again well, I will take the earliest opportunity to do myself the pleasure to write to my Sweet Cousin Ella

My kindest regards to your Mother Father & family-yr aff Cousin Lewis-

Whatever correspondence ensued between the two after this letter was written, to date, has not been found. A letter does exist written from Lewis to John Augustine Washington III 3 informing him of his impending marriage to “our sweet cousin Ella Bassett.”

In the year following their marriage, 1861, political events dividing the country came to a head with war. Both Lewis and Ella were ardent supporters of their home state and when Virginia joined the Confederate States of America, they sided with the new rebel government. For reasons unknown, Lewis was consistently rejected by the Virginia government as well as that of the CSA for a commission as an officer.

As nearby Harpers Ferry changed hands from Federal to Confederate and then back again, with troops of both sides moving in and around the estate, Beallair became untenable. To add to the problem, Ella was now pregnant and not having an easy time with her situation. Therefore, they moved to her parents’ place at Clover Lea. On August 21, 1861 Ella gave birth to Betty Lewis Washington.

As nearby Harpers Ferry changed hands from Federal to Confederate and then back again, with troops of both sides moving in and around the estate, Beallair became untenable. To add to the problem, Ella was now pregnant and not having an easy time with her situation. Therefore, they moved to her parents’ place at Clover Lea. On August 21, 1861 Ella gave birth to Betty Lewis Washington.

In the spring of 1864, the war returned to Virginia with a vengeance. Clover Lea became embroiled in the conflict even more than previously as battles raged very close to the homestead. Ella’s much younger sister, Annette, was preparing to leave for her own safety when Federal pickets rode by. Lewis hid in the woods fearing he might be caught in the home. Ella fixed him a basket of lunch to take along. With all appearing to be clear, Ella had Lewis return to the house for dinner. A rush of Federal cavalrymen riding by the house soon had Lewis fleeing into the woods again.

By now, Lewis knew with so many Union troops in close approximation, he had to leave for good. One possibility is that he had finally received favorable notification that his services to the Confederacy were desired for him to serve as an emissary to France. Lewis decided to leave with Annette but could not take Ella since she had to care for their baby son.

As the weeks wore on, after several more encounters, the Union army moved away. Ella confided her longing for Lewis in her diary:

“I am feeling physically and mentally oppressed, never found my nerves so shaken, and my courage so tried as before… it is this separation from my dear husband, not even hearing from him, that saddens, and tries me.”4

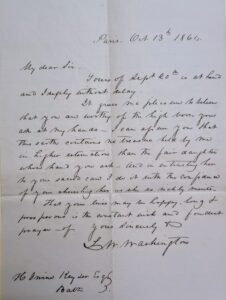

Unfortunately, no correspondence has been found to know whether or not Lewis and Ella were able to communicate. However, one of the letters in the Jefferson County Museum’s collection serves as proof that Lewis had, indeed, made it to Paris. The Jefferson County Museum has his response to a request from wealthy Baltimore businessman Henry Irving Keyser for Lewis’s permission to marry his daughter Mary Ann Washington, dated October 13, 1864. His consent was immediately granted saying, “It gives me pleasure to believe that you are worthy of the high boon you ask at my hands…”5

Below is a transcription of the letter:

Paris, Oct 13th 1864

My dear Sir-

Yours of Sept 20th is at hand and I reply without delay.

It gives me pleasure to believe that you are worthy of the high boon you ask at my hands-I can assure you that this earth contains no treasures held by me in higher estimation than the fair daughter whose hand you ask-And in entrusting her to your sacred care I do it with the confidence of your cherishing her as she so richly merits.

That your lives may be happy, long & prosperous is the constant wish and fondest prayer of yours sincerely &c.

L. W. Washington

H. Irvine Keyser Esq.

Balt.

Meanwhile, the war dragged on for nearly another year until finally ending with the defeat of the Confederacy. Ella and her young son temporarily lived in a boarding house in Georgetown while she endeavored in her main concern to get Lewis back. Only a pardon from the government would allow this return. Through her influence as a Washington and through family connections like George Armstrong Custer, she personally appealed to President Andrew Johnson and finally secured the necessary pardon. When word got out of Ella’s success, she was soon besieged with pleas from other former Confederate sympathizers to gain pardons for their loved ones who were in similar circumstances. She became well known in Washington as she made a business of securing these pardons and put the money aside to use to regain the estate at Beallair.

During the war, the federal government had declared the Beallair manor house abandoned and had leased it to a tenant who refused to leave. Thus, Ella began what was to become a series of court cases that she successively won to regain the property and its furnishings. She had to be the leader in this enterprise, for Lewis returned home a broken man. He had invested all he had and shared in the downfall of the Confederacy. Because of his Confederate support, northern newspapers disparaged his reputation with stories of English sympathies, barroom pugilistic antics and even intimation that Lewis had a drinking problem.6 Aside from these difficulties, the painstaking efforts of Lewis and Ella to make the farm profitable failed.

When Lewis died on October 1, 1871, it fell upon Ella to make the hard choices to maintain the Beallair estate and to cover the debts. Her pardon business had died out due to the government giving blanket pardons to former Confederates. Her wins in court did not give her enough return and, in desperation, she had to sell the artifacts of George Washington that had been passed down through the family (which were briefly stolen by John Brown’s raiders in 1859) to the New York Library Museum in 1873. Even though the items brought in a worthy sum, it was not enough to cover the accumulated debt. In 1877, Ella was ordered by the West Virginia court to sell the property to its most interested buyer, former Union officer George Washington Ziegler Black.

When Lewis died on October 1, 1871, it fell upon Ella to make the hard choices to maintain the Beallair estate and to cover the debts. Her pardon business had died out due to the government giving blanket pardons to former Confederates. Her wins in court did not give her enough return and, in desperation, she had to sell the artifacts of George Washington that had been passed down through the family (which were briefly stolen by John Brown’s raiders in 1859) to the New York Library Museum in 1873. Even though the items brought in a worthy sum, it was not enough to cover the accumulated debt. In 1877, Ella was ordered by the West Virginia court to sell the property to its most interested buyer, former Union officer George Washington Ziegler Black.

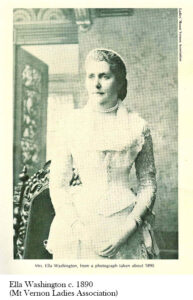

Ella and her son then went back to Clover Lea. She never lost her fondness for Beallair and visited it often. She became a family favorite of the Blacks and was a welcome guest. Ella’s developed talent for writing led to her being published many times in newspapers and magazines with her various short stories and poems. She also put out a well-accepted biography of Mary Ball Washington. She was an active member of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association and did much to preserve and furnish this home that became a national monument. Perhaps by carrying on all she could to preserve the Washington name, she was also reliving her love for Lewis. In any case, she managed to live the remainder of her life with purpose.

Ella’s final days were spent living in New York until her death on January 17, 1898. Her last wish was granted when she was buried next to her husband Lewis in Mount Zion Cemetery in Charles Town. They now lie for eternity side-by side. Their marriage only lasted eleven years yet they remained steadfast to one another despite the events that tested their love.

1 Newspaper advertisement December 12, 1844.

2 Washington, Lewis, Letter of October 30th, 1859. Jefferson County Museum. Charles Town, West Virginia.

3 Mount Vernon Papers. Letter to John Augustine Washington III September 25, 1860. Box 77, Folder 1860.09.25. Identifier: 2017-SC- 008-013.

4 Ibid. June 10, 1864.

5 Washington, Lewis, Letter of October 13, 1864. Jefferson County Museum, Charles Town, WV.

6 Belmont Chronicle, November 23, 1869. Clairsville, Ohio, page 2.

—————

Lawrence J. Bopp is a retired history teacher from Baltimore County, Maryland, author of several history books, particularly on the USS Constellation, a reenactor of everything from 1634 to World War II, and an avid researcher and historian. He is now a resident of the Beallair community, where he wrote directed and produced a video history of Beallair in 2021. Inspired by a posted letter from Lewis Washington to his future bride Ella Bassett, Mr. Bopp volunteered to assist the Jefferson County Museum by researching and developing some blogs based on letters in the museum collection. These blogpost is the first in a series.